By Professor Louis René Beres and General John T. Chain (USAF/ret.)

In world politics, irrational does not mean “crazy.” It does mean valuing certain goals or objectives even more highly than national survival. In such rare but not unprecedented circumstances, the irrational country leadership may still maintain a distinct rank-order of preferences. Unlike trying to influence a “crazy” state, therefore, it is possible to effectively deter an irrational adversary.

Iran is not a “crazy,” or wholly unpredictable, state. Although it is conceivable that Iran’s political and clerical leaders could sometime welcome the Shiite apocalypse more highly than avoiding military destruction, they could also remain subject to alternative deterrent threats. Faced with such circumstances, Israel could plan on basing stable and long-term deterrence of an already-nuclear Iran upon various unorthodox threats of reprisal or punishment. Israel’s only other fully rational option could be a prompt and still-purposeful preemption.

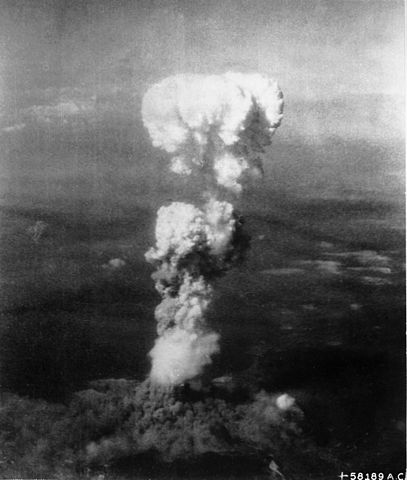

At the time this photo was made, smoke billowed 20,000 feet above Hiroshima while smoke from the burst of the first atomic bomb had spread over 10,000 feet on the target at the base of the rising column (6 August 1945).

Additionally, because of the prospect of Iranian irrationality, Israel’s military planners will have to identify suitable ways of ensuring that even a nuclear “suicide state” could be deterred. Such a perilous threat may be very small, but, with Iran’s particular Shiite eschatology, it might not be negligible. And while the probability of having to face such an irrational enemy state would probably be very low, the disutility or expected harm of any single deterrence failure could be very high.

Israel needs to maintain and strengthen its plans for ballistic missile defense, both the Arrow system, and also Iron Dome, a lower-altitude interceptor designed to guard against shorter-range rocket attacks from Lebanon and Gaza. These systems, including Magic Wand, which is still in the development phase, will inevitably have leakage. It follows that their principal benefit would ultimately lie in enhanced deterrence, rather than in any added physical protection.

A newly-nuclear Iran, if still rational, would need steadily increasing numbers of offensive missiles in order to achieve a sufficiently destructive first-strike capability against Israel. There could come a time, however, when Iran would be able to deploy more than a small number of nuclear-tipped missiles. Should that happen, Arrow, Iron Dome and, potentially, Magic Wand, could cease being critical enhancements of Israeli nuclear deterrence.

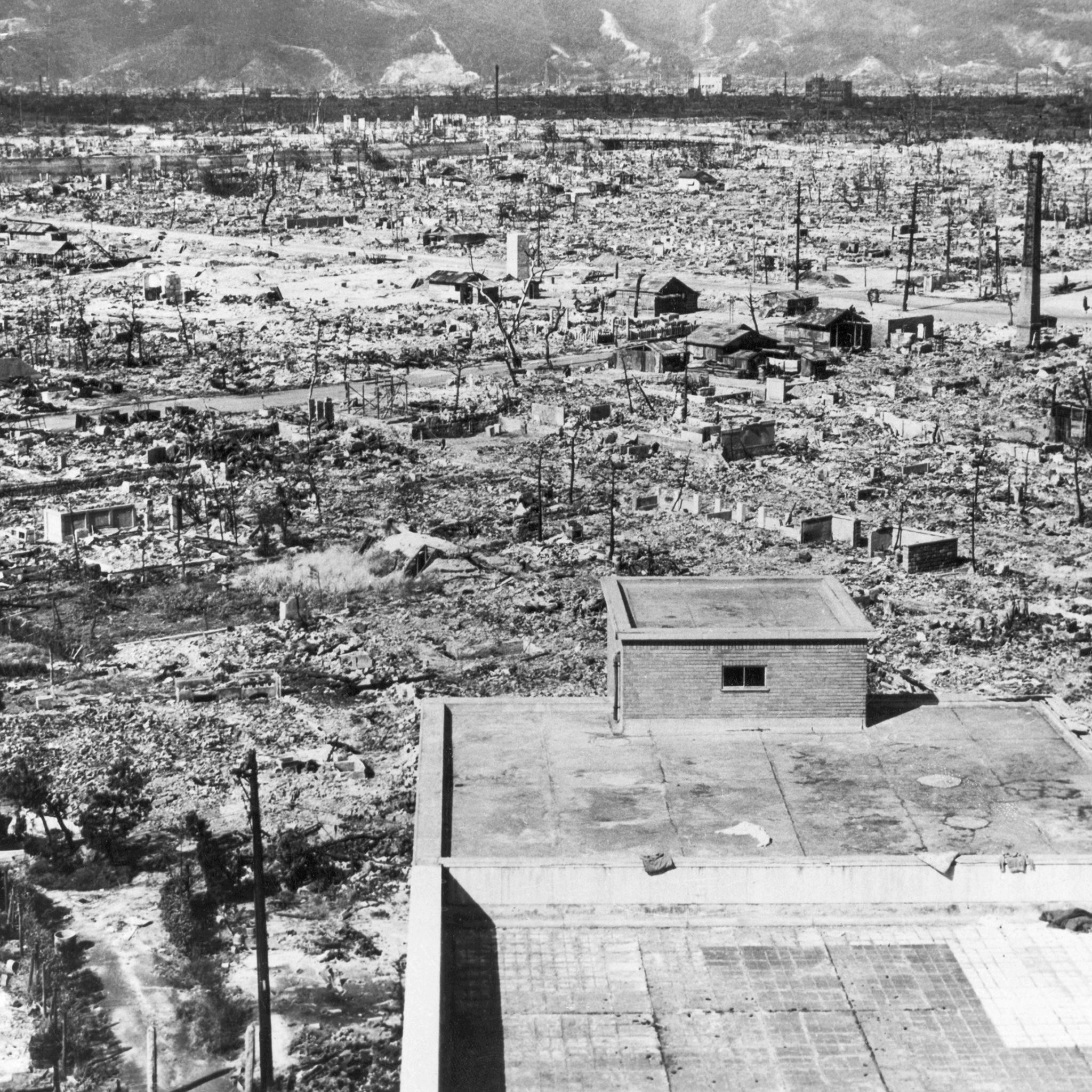

Impact of the nuclear bomb drop on Hiroshima. From the top of the Red Cross Hospital looking northwest (1945).

In such unprecedented circumstances, Israel’s leaders would need to look closely at two eccentric and more-or-less untried deterrence strategies, possibly in tandem with one another. First, these leaders would have to understand that even an irrational Iranian leadership could have distinct preferences, and even hierarchies of preferences. Their task would be to determine precisely what these particular preferences might be (most likely, they would have to do with certain presumed religious goals), and how these preferences are apt to be ranked in Tehran.

Second, Israel’s leaders would have to determine the likely deterrence benefits of their own pretended irrationality. An irrational Iranian enemy could be less likely to strike first if it felt Israel’s decision-makers were irrational themselves. Years ago, General Moshe Dayan, then Israel’s Minister of Defense, said: “Israel must be seen as a mad dog; too dangerous to bother.” Here, Dayan revealed an intuitive awareness of the possible benefits to Israel of feigned irrationality.

There is a prior point. Before Israel’s leaders can proceed with any usable plans for deterring an irrational nuclear adversary, especially Iran, they must first be convinced that this adversary is, in fact, genuinely irrational, and not merely pretending irrationality.

The early sequencing of this vital judgment cannot be overstated. Because all specific Israeli deterrence policies must be premised upon the presumed rationality or irrationality of nuclear enemies, determining precise enemy preference and preference-orderings should become the very first phase of strategic planning in Tel-Aviv.

Soon, facing the prospect of a nuclear Iran, Israel must select refined and workable options to deal with two separate but interpenetrating levels of danger. Should Iranian leaders be judged to meet the usual tests of rationality in world politics, Israel will have to focus upon reducing its nuclear ambiguity, on taking its bomb out of the “basement,” and on operationalizing a retaliatory force that is adequately hardened and dispersed. This second-strike nuclear force should be recognizably ready to inflict “assured destruction” against identifiable enemy cities.

Where Israel’s leaders determine that they may have to deter an irrational enemy leadership in Tehran or elsewhere, they will also have to consider the possible strategic benefits of appearing as a “mad dog,” or a strategy of pretended irrationality. Together with any such consideration, both Jerusalem and Tel-Aviv, civilian leadership and military, will need to determine what exactly is valued most highly by Israel’s pertinent enemies, and then prepare to issue fully credible threats to these core enemy preferences.

Whether Iran’s leadership is expected to be rational or irrational, Israel will need to continue with its expanding programs for cyber-defense and cyber-war.

Perhaps a nuclear Iran can still be prevented by preemption. But in the more likely absence of any remaining options for “anticipatory self-defense,” Israel’s best available stance will be to effectively deter an already-nuclear Iran. To succeed, Israel’s leaders will first have to determine whether their adversaries in Tehran are rational, irrational, or “crazy.”

Louis René Beres (Ph.D., Princeton, 1971) is Professor of Political Science and International Law at Purdue University. The author of many major books and articles in the field, he was Chair of Project Daniel (Israel).John T. Chain (USAF/ret.) was Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Strategic Air Command (CINCSAC), and Director, Joint Strategic Target Planning Staff. General Chain has also served as Chief of Staff, Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe, and as Director, Bureau of Politico-Military Affairs, U.S. Department of State.http://blog.oup.com/2012/02/israel-iran-nuclear/

No comments:

Post a Comment