Why anti-Zionism is still anti-Semitic: reply to critics

Last week, I penned an analysis of why anti-Zionism is inherently anti-Semitic: the proposition it is anti-Semitic to “deny… the Jewish people their right to self-determination“, as expressed in the EU working definition of anti-Semitism, stood in need of explanation. The gist of my analysis was that anti-Zionism, expressed as a desire for the disappearance of the State of Israel, is an ideology that demands that Jews be retroactively stripped of their right to self-determine; that treats Jews as political inferiors by only allowing them to participate in political society as minorities; and that is content to expose Jews to dangers in a post-Israel world for which anti-Zionists attempt to offer no solution.

The article caused quite a stir: some people thought I had gone too far; others, not far enough. The responses were mostly civil, notwithstanding some anti-Semitic name-calling: who knew the “ugly narcissistic hook nosed children of Cain” are “the absolute best at the art of misdirection“? The reason why it was anti-Semitic of others to compare Zionism to Nazism, associating the victims of the Holocaust with their persecutors, should be self-evident.

Nevertheless, it was obvious that many of the people who criticised me had not read the article in its entirety: I was accused, for example, of suggesting that criticism of Israeli policy is anti-Semitic, which would obviously be stupid, which is why I explicitly disavowed this position, except for the cases of usage of classically anti-Semitic tropes.

I was also accused of playing the anti-Semitism card in order to shut down debate (that trope again!), despite ending with an invitation for readers to share their criticism. I guess I must have been been trying to cover up my conspiracy to shut down debate by disingenuously seeking to generate debate: we Jews Zionists are so sneaky! (#JewishConspiracy?)

This follow-up piece is a reply to my critics. I’ll begin by clarifying some misconceptions about the general argument, before getting to grips with some really interesting challenges from readers. My bottom line, however, remains intact: anti-Zionism, defined as the doctrine that the State of Israel should be destroyed or dissolved, is inherently anti-Semitic.

Addressing Challenges to the Thesis

One common criticism was that I had mischaracterised anti-Zionism, either by construing it too narrowly or too expansively: “his critique of anti-Zionism,” one reader responded, “is applicable only in the way that he chose to define Zionism“. Sound analysis, however, requires one to define terms before analysing them: so whatever falls outside my definitions is therefore also beyond the scope of my criticism. Positions labelled ‘anti-Zionist’ that nevertheless accept Israel’s existence are outside the discussion, which I explicitly and legitimately limited to the dominant paradigm within anti-Zionism. If you call yourself anti-Zionist but do not incite Israel’s destruction, then relax: I’m not calling you an anti-Semite.

Someone also claimed that anti-Semitism does not mean prejudice against Jews but against all Semitic peoples, including Arabs. Frankly this is a bit silly, not only because in cutting against the historical usage of the term, it seeks to redefine it, but also because hatred of all Semitic peoples simply isn’t a thing. If there were a unified tradition of prejudice towards Arabs and Jews as a collective, then there would be a phenomenon in want of a name, but this isn’t the case. Anti-Semitism pertains to prejudice against Jews, and anti-Zionism is a form thereof.

A fascinating query highlighted the connections between Zionism and anti-Semitism, noting that recognition of a distinct Jewish people has historically been motivated in part by anti-Semitism, which made it easier for countries to exclude and “export” Jews rather than integrating them. This is a powerful point: Zionism was indeed a response to the framing of Jews by anti-Semites as the Other. If Jews had never been denigrated as outsiders, it is unlikely they would have sustained a conception of themselves as such over two millennia. Indeed, the yearning for a homeland makes no sense outside the context of homelessness. That’s why Jewish anti-Zionism is strongest among those who feel most at home in their own countries: they feel like they already belong, so do not see themselves as exiles. As a perverse consequence, therefore, Zionism itself can be perversely anti-Semitic if expressed as a desire to banish Jews elsewhere: did the Nazis not wish to exile European Jews to Madagascar?

None of this, however, changes the fact that if Jews currently self-identify as a people, and the international community has recognised political independence as the legitimate manifestation of the rights that follow, then the revocation of these rights is a matter of discrimination against Jews as Jews, and hence is anti-Semitic.

“Imagine there’s no countries…” Not anti-Semitism, surely?

Another claim was that anti-Zionism can be opposed out of antagonism to the basic idea of the nation-state or self-determination, emerging from cosmopolitan or internationalist concerns. If you want a world without borders, then there are safer borders to take down first. Anti-Zionism, however, does not pick on Israel to take the lead in the universal dissolution of states: it is the position that in a world of nation-states, the Jewish nation-state should be nullified. The doctrine does not call for the abolition of states, but for the replacement of one state with another. It is the position that every nation that the international community has recognised should have a state, should keep its state – bar one: the Jews. That’s why it’s anti-Semitic.

If the anti-Zionism of cosmopolitan internationalists is merely subsidiary to a sincere, loftier vision of a world without borders, then so long as it has an answer for how the safety of Jews can be guaranteed in the radical new world order, it may be an exception, no matter how muddled and hopelessly idealistic, to the broader rule of anti-Semitism.

So much for distractions. Onto the meatier challenges.

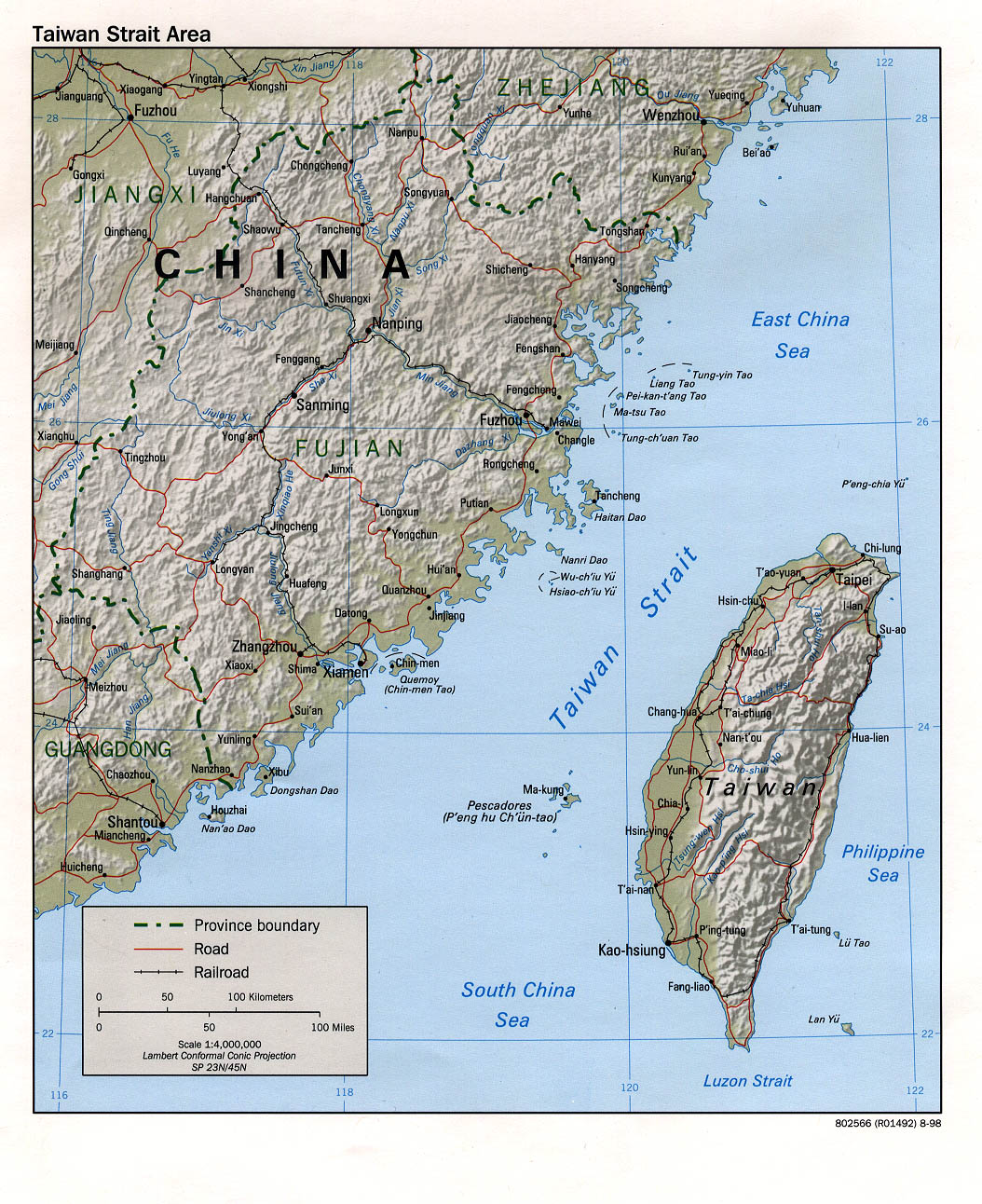

One intriguing challenge to my thesis drew an analogy to the retroactive non-recognition of Taiwan. After the Chinese Civil War, two political groups claimed to be the legitimate government of China: the Communist Party, which controlled the mainland, and the Nationalists, which had retreated to the island of Taiwan. At first, the international community recognised the regime in Taiwan as the legitimate government of China, but in 1971 this honour was transferred to the Communist-run People’s Republic of China; Taiwan was stripped of its seat at the United Nations. If it was not racist for the international community to revoke Taiwanese statehood, why would it be racist in the case of Israel?

Didn’t the world revoke Taiwan’s statehood once?

This line of attack stumbles on an important disanalogy. Taipei and Beijing host separate regimes that claim to represent the whole of China: they agree that there is only one China, but differ over the identity of its legitimate government. Taiwan does not think that its statehood was revoked, because it had never claimed statehood in the first place as a separate entity from China: the world simply recognised another government over a territory that both sides consider indivisible. Similarly, many countries recently recognised the National Transitional Council as the legitimate representative of the Libyan people, while Gaddafi still claimed that mantle: they recognised a new government, not a new country. In short, Taipei and Beijing accept a one state solution, and disagree on who will run it.

The difference with the Israel-Palestine conflict is striking, for Jerusalem and Ramallah are committed a two-state solution: Israel has never formally annexed the Palestinian territories; the Palestinians, meanwhile, have recognised “the right of the State of Israel to exist in peace and security“. Neither side claims sovereignty over the whole land or insists that only one of them can form a legitimate government. The international community recognises a separate state called Israel; many states also recognise a Palestine. So the one-state solution would involve an effective revocation of statehood, unlike with Taiwan: anti-Zionism, therefore, cannot take comfort in this precedent.

A further major criticism was that Zionism is inherently inconsistent with liberal theories of the state; as a liberal, I take this criticism very seriously. The argument is that the ‘Jewish and democratic’ formula is a contradiction in terms: the two pillars of Israel’s identity cannot be logically reconciled, and since only democratic states can be morally legitimate, it is clear which one has to go. This is a conclusion that Zionists are desperate to avoid: to side with one value to the exclusion of the other would be, as Meretz MK Nitzan Horowitz put it beautifully, “like choosing between your father and your mother”.

So long as the tension between the two identities has little practicalimport, however, the allegation loses steam: if the two identities never clash over substantive issues, there is simply no problem. Israel can continue to function as any other democracy, but with a Jewish majority: a country “as Jewish as England is English“, as Chaim Weizmann envisioned. Attempts to impose Jewish law or give preferential civic rights to Jews would indeed be an affront to democracy, but they are policy choices rather than inherent questions of Israel’s self-definition, so criticism would not be anti-Zionist at all.

.jpg)

Israel pulled out of Gaza explicitly in order to stop ‘Jewish’ and ‘democratic’ coming into contradiction

Sometimes the prospect of an unpalatable choice presented by a future contradiction between the Jewish and democratic forces Israel to make certain policy choices, which is why even Prime Minister Netanyahu will countenance Palestinian statehood, to avert the spectre of the binational state. Ariel Sharon had already grasped the basic truth that “it is impossible to have a Jewish, democratic state and at the same time to control all of Eretz Israel”, which is why he authorised the disengagement from Gaza. These decisions are meant to ensure that the potential clash between the two core values never be actualised.

A problem might arise if changing demographics within Israel-proper forced Jerusalem to prioritise one of the two values. Note, however, that the problem would arise not from Israel’s self-definition per se, but from its collision with the unique situation facing Israel: a growing national minority, relatively homogeneous, resistant to integration and harbouring a very different vision of the state’s basic identity. Minorities in Western states are mostly heterogeneous; national minorities remain comparatively small. Concerns arising from the Jewish part of Israel’s identity would arise from a conjunction of a Western nation-state-style definition with problems that other nation-states do not face. I do not know what Israel should do if forced to choose between Jewish and democratic, but no other state is required to stipulate what it would do in a hypothetical dilemma to avoid allegations of racism. One wonders how India would react if its Muslims were set to form a majority, which might entail a union with Pakistan – but this isn’t an issue. Hypothetical problems are not real problems so long as they are only theoretical.

What lessons can Israel learn from the jurisprudence of the Canadian Supreme Court about balancing competing values?

In the meanwhile, however, Canada offers an intriguing insight into how a modern democracy can self-define in terms of multiple values that are constitutionally co-equal with democracy. In 1998, the Canadian Supreme Court was asked to pre-emptively answer legal questions about the possible secession of Quebec from Canada; it replied with a powerfully nuanced analysis of the Canadian constitution.

The Court identified “federalism, democracy, constitutionalism and the rule of law, and respect for minority rights” as Canada’s ”four foundational constitutional principles”. It went on to explain: “These defining principles function in symbiosis. No single principle can be defined in isolation from the others, nor does any one principle trump or exclude the operation of any other.” Quebec and Ottowa would be compelled to negotiate over independence “in accordance” with these co-equal principles, none of which had absolute priority over others.

The principle of holding multiple values as co-equal with democracy is not an anomaly in international jurisprudence. Israel can aspire to a similar balancing-act between the Jewish and democratic: both could be assigned equal importance, with dilemmas resolved in a Canadian-style spirit of reconciliation of values. Perhaps this answer will not please everyone: the question certainly deserves more attention and nuance than it can be given in a few paragraphs here. The government recently commissioned Professor Ruth Gavison to draft a definition of this troubled formula; it will be interesting to read her proposals.

Anti-Zionism, however, is weak on the ground in its claims that Zionism is necessarily an affront to liberal values, at least as presently practised. Israel’s Declaration of Independence, perhaps the most authoritative expression of Zionist ideals, is emphatic in its belief that Jewish statehood is perfectly consistent with “full and equal citizenship” for minorities, and that far from being one horn of a dilemma, “freedom, justice and peace” are quintessential parts of Israel’s Jewish character, rather poetically “envisioned by the prophets of Israel”.

Perhaps Israel has fallen short of the high bar it set itself, but criticism of its policy is one thing: calls for its destruction are another. I should stress, moreover, that even if one maintains that the principle of Jewish statehood is problematic, calls for a one-state solution do not logically follow. If Zionism renders Israel inconsistent with liberal ideals, it is highly doubtful that a one-state solution would bring it closer into consistency: perhaps those who think a binational state would be a liberal paradise should take a look at who won the last Palestinian elections, then think again. If liberals want to see the actualisation of liberal values, supporting Israel’s right to exist should be a no-brainer.

The Challenge to Anti-Zionism

If anti-Zionism wants to be an intellectually respectable position, it needs to directly address the charges against it by answering these questions:

1. Which other nations have lost their right to self-determine through their conduct, or are the Jews singularly evil? Alternatively, which other countries that should not have been created should also have their independence reversed?2. With the horrors of persecution fresh in living memory, is it reasonable to expect Jews to exchange the sovereign equality they presently enjoy for permanent subordination to the very states that once persecuted them?3. How will anti-Zionists fully guarantee Jews’ personal safety from anti-Semitic persecution after they revoke the right of Jews to be the ultimate guarantors of their own security?

It’s just not good enough to fall back on the old canard that Jews only equate anti-Zionism with anti-Semitism in order to to silence dissent. Far from it: I want to hear these people account for themselves. Anti-Zionists must answer these three questions head-on if they are to purge the stench of anti-Semitism that is so redolent in their ideology.

Something tells me they will fail.

Read the original article here: “Why anti-Zionism is inherently anti-Semitic”

http://blogs.timesofisrael.com/why-anti-zionism-is-still-anti-semitic-reply-to-critics/

No comments:

Post a Comment