What the Fight in Israel Is All About

Why are Israel and Palestine fighting?

The fight between Jews and Arabs over Israel and Palestine goes back to 1922. The Romans had given Palestine its name when they conquered it from the Jews nearly 2,000 years earlier. After the Romans were thrown out Palestine was part of one Arab or other Moslem empire after another since the 7th century. Finally, in the 400 years before it became available in 1922, Palestine had been a small part of the Turkish Ottoman Empire. But in World War I the British and French defeated Germany and the Ottoman Empire and stripped them of their colonies. Thus the League of Nations had to decide what nations should become sovereign in Palestine and the rest of the vast lands lost by the Turks. The League awarded more than 90% of these lands to Arab states, with Britain and France as temporary trustees.

But there were two claimants to sparsely populated Palestine. The Arab countries insisted that since it had been ruled by Moslems for more than a millennium, and since its small population of less than a million inhabitants were mostly Arabs, Palestine should become part of an Arab country, presumably Syria. The British government, following the policy it had announced 5 years earlier in the Balfour Declaration, urged that Palestine be set aside as the site for a homeland for the Jewish people. They argued that Jewish kingdoms had ruled various parts of Palestine for over a thousand years and that the land and especially Jerusalem the ancient Jewish capital were central to the Jewish religion. Furthermore they pointed out that the Jewish people had been praying to return to the land for nearly 2,000 years, and that throughout those millennia there were always Jews living in the land and returning to the land. They added that while the Arabs had a number of countries, with millions of square miles, the Jews suffered from having no homeland at all. Also the small numbers of Jews who had come to Palestine in previous decades had begun to build up the country – attracting many Arabs from neighboring countries – and that the Jews could be expected to provide economic development and a lawful society which would help the development of the whole region.

At the time no one suggested turning the land – which had never been a separate country—over to the Arabs who lived there, who were not thought of as a separate people. The inhabitants thought of themselves as Moslems, or in a few cases as Christians, and as Arabs. They had loyalties to family and clan, but not to the region of Palestine which had been divided into various Ottoman districts, in none of which had Jerusalem been the capital.

Despite the claim of the Arab countries, and the fact that most inhabitants were Arabs, the League of Nations ruled that Great Britain should become the Mandatory government of Palestine to provide for Jewish settlement of the land so that it could again become the site of a Jewish homeland. It was widely believed that the Jews needed a homeland to be protected from persecution. The League also provided that the British should protect the local inhabitants’ civil rights – as distinguished from political or national rights.

The Arab countries and the local Arab residents did not accept the decision of the League of Nations – although they did not deny the authority of the League from which they had received so much benefit. Concerning Palestine the Arabs have never accepted any international decision. Nor have they been willing to negotiate or to accept any division or compromise. From the beginning their position has been that this is all “Arab land” or “Palestinian land” and they have refused to negotiate or to recognize any ruling to the contrary. (As part of the Oslo process they said that they were willing to make a compromise, but when negotiations came to a head at Camp David in 2000 they refused to make any counter-offers and instead began the current terror offensive three months later.)

Whether or not the League of Nations was wrong to decide that Palestine should become a Jewish homeland, the effect of that decision is that the hundreds of thousands of Jews who came to Palestine from the creation of the Mandate in 1922 until the birth of the State of Israel in 1948 came pursuant to the international law that existed at the time. They came not as colonials, and not to take land away from another people, but to fulfill the decision of the League of Nations that Jews should be encouraged to settle in Palestine. And they bought the land on which they settled. The Arabs who fought against the Jewish settlers and refugees may have thought of themselves as protecting their own country from invaders, but according to international law it wasn’t their country (and it never had been in the past) and they were fighting against the existing law.

In fact there has never been any “Palestinian land” anywhere because there has never been a Palestinian country. But a majority of the people of the Kingdom of Jordan, which had been created out of the Eastern part of Mandatory Palestine, are Palestinians. While Arabs – that is native Arabic-speakers who consider themselves part of Arab history – had been a majority in Palestine for hundreds of years before it became part of the Ottoman Empire, Palestine had never been a separate Arab country; it had always been an unseparated part of other countries or empires. Except for Egypt, the idea of separate Arab countries – or nationalities – distinct from Islam or Arab – is less than two centuries old. Palestine had been an “Arab land” only in the sense of being part of various Arab empires, just as it had been part of Egyptian or Persian or Greek empires before. But no Arab government had paid much attention to Palestine or to Jerusalem. And no government that had ever been sovereign in Palestine since the Jewish kingdoms now claims the land.

Under the British Mandate hundreds of thousands of Jews accepted the invitation to settle in Palestine. But the Arabs refused to accept the League’s Mandate and fought against the Jewish settlers. The British Mandatory government was unwilling to devote the necessary resources to enforce the law and the Jews often had to defend themselves to avoid being killed. Some years later when Britain was defending itself against the onslaught of Hitler’s Germany it felt that it needed help from the Arab countries. Therefore despite the Jews need for a place to go to escape from murder by the Germans, and despite the British responsibility under the Mandate to use Palestine as a homeland for the Jews, Britain yielded to Arab pressure and refused to allow Jews to escape to Palestine, and as a result hundreds of thousands of Jews who could have been saved were killed by the Germans.

In 1945 after the end of World War II great pressure was put on Britain to allow the Jewish survivors of the holocaust to come to Palestine, but because of their political interests the British continued to obey the Arab demand to exclude the Jews despite the provisions of the Mandate. The Palestinian Jews began a guerrilla war against the British government and by 1947 the British decided that they would give up their Mandate and go home. To deal with the potential vacuum of authority the UN General Assembly recommended that Western Palestine be divided into two new states, one Jewish and one Arab, with Jerusalem to be an international territory for ten years. (Eastern Palestine had earlier been separated and given to King Abdullah to become Jordan.)

Contrary to a common impression the Jews were not given Palestine as compensation for being victims of the Holocaust. Palestine had been established as a Jewish homeland by the League of Nations a generation earlier. After the Holocaust the UN suggested a smaller territory for the survivors of the Holocaust and for the Jewish people than had been set by the League. And Israel actually got only the land its forces succeeded in holding in the fighting against the Arab armies. No land was given to Israel because of the Holocaust or as a result of a UN decision.

In the UN discussions the Arab countries had opposed both making Palestine a single binational state for Arabs and for Jews, and dividing it into two states. They insisted that it become a single Arab country. And they refused to accept the UN recommendation that two states be created, and did not allow the new Arab state recommended by the UN for part of Palestine to come into existence. Instead, on the day that the British Mandate expired five Arab countries sent their armies into Palestine to eliminate the Jews and divide the land among themselves.

The Jewish community in Palestine accepted the UN recommendation to divide Palestine and declared the State of Israel and its willingness to give its Arab inhabitants equal rights and to live in peace with its Arab neighbors. But from its first day Israel had to fight to exist. It was under attack by Arab armies who took whatever land they could, regardless of the UN partition recommendation, and killed or removed all Jews from whatever land they occupied.

The fighting continued, off and on, for over a year until the UN finally succeeded in negotiating an armistice along the lines the forces held when the fighting stopped. These borders lasted from 1949 until 1967 and are called the ’67 borders. The Armistice left Western Palestine divided into three pieces: Israel, the Gaza strip, which is a small piece of land along the Mediterranean shore which was occupied by the Egyptian army but not incorporated into Egypt, and “the West Bank,” the part of the Mandate territory between Israel and the West of the Jordan River, which was occupied by Jordan. Jordan tried to incorporate the West Bank into Jordan – changing its own name from Transjordan, but none of the Arab countries recognized the area as part of Jordan. The only countries which recognized Jordan’s claim were Britain and Pakistan, and later Jordan gave up its claim.

During the 1948-9 war, between Israel and the Arab states which attacked Israel, about 600,000 Arabs who had been living in the area which became Israel left their homes for neighboring Arab countries. Some were forced to leave by the Israeli army, but the majority left to avoid the fighting and because they were urged or even forced to do so by the Arab governments and their own leaders, despite the fact that many were urged by their Jewish neighbors to remain and live in peace in Israel. These 600,000 were the start of “the Arab refugee problem.”

Because of the creation of Israel and the Arab war against it, Jewish communities in Arab countries, some of which dated back more than a thousand years, were uprooted, and more than 600,000 Jews were forced to leave their homes and property in Arab countries. Almost all of these Jewish refugees settled in Israel, which also accepted about an equal number of refugees from Europe. During its first few years tiny Israel, with an initial population of only about 600,000 Jews, and an area about the size of New Jersey, took in over a million refugees.

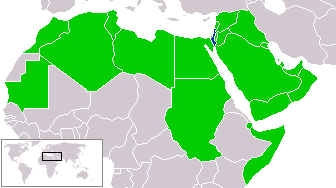

The Arab countries, with a population of over 50 million and an area bigger than the U.S., refused to accept any Arab refugees, even though they spoke the same language, shared the same culture, and practiced the same religion. While they couldn’t fight militarily at the time, the Arab countries continued their effort to destroy Israel in other ways. They knew that keeping the Arab refugees in refugee camps, and not allowing them the choice of resettling in Arab countries, would preserve those people as a weapon against Israel.

In the years after World War II there were more than 20 million refugees in all parts of the world and all of them were resettled except for the .6 million Arab refugees. The Arab refugees were made to continue as refugees, mostly in camps, by the Arab countries in order to serve these countries’ war against Israel. Their number has grown in the last 50 years to over 3 million. They are the fastest growing population in the world, and the biggest practical obstacle to achieving a settlement of the Israeli-Arab conflict.

In the Spring of 1967 the Arab countries, led by Gamal Abdul Nasser of Egypt, prepared to attack Israel and, in their own words, “throw the Jews into the sea.” The UN forces stationed between Egypt and Israel in the Sinai desert obeyed Nasser’s demand to get out of his way, and the Egyptian military moved into the Sinai toward Israel. Egypt closed the Tiran Straits to ships going to or from Israel, refusing all diplomatic efforts by the US to fulfill the US commitment to Israel to keep its sea lanes open.

Before the Egyptian attack was launched Israel preempted with air attacks that destroyed most of the Egyptian air force, and with armored attacks into the Sinai. At the same time Israel notified the King of Jordan that Israel would not attack the territory he occupied and urged him to maintain peace with Israel. Jordan, however, yielded to Arab pressure and joined the attack against Israel sending its army against Jewish Jerusalem.

The result was that in six days Israel’s armies threw Egypt out of Gaza and the Sinai, threw Jordan out of Jerusalem and the West Bank, and threw Syria out of the Golan Heights, from which they had been shooting at Israel from time to time since 1949, and very heavily during the six-day war, thus the area controlled by Israel was more than tripled.

The UN Security Council effort to resolve the war resulted in UNSC Resolution 242 which called on the Arab states to make peace with Israel and left the question of borders to be resolved by negotiations between the parties on the basis of two guidelines: that the borders be “secure and recognized” and that Israel remove its forces from “territories” that they had occupied in the war. The Security Council rejected proposals to change the word “territories” into “all the territories” or into “the territories.” (The French, Arab, and Russian translation of the Resolution used the phrase “the territories,” but the UN practice in case of conflict between different translations is to follow the language in which the Resolution was negotiated, which was English.)

To this day the Palestinians and all the Arab countries insist that UNSC Res. 242 requires that Israel get out of all the territories acquired in 1967, just as they continue to insist that the League of Nations Mandate to create a Jewish homeland in Palestine was invalid. But Lord Caradon of England, and Eugene Rostow of the U.S., two of the principal diplomats responsible for negotiating the Resolution, and most independent international legal experts, have written that Res 242 was not intended to, and does not, require Israel to return to the ’67 borders. Such a requirement would be inconsistent with the phrase “secure and recognized” borders, both because those borders are not secure and because no description of the borders would be needed if the Resolution were referring to the preexisting borders.

After the Security Council passed Res. 242 the Arab countries met at Khartoum and issued their famous “three noes:” no negotiations, no recognition, and no peace. But ten years later, in 1977, President Sadat of Egypt, after being secretly assured by Israel that it was willing to return the Sinai to Egypt, came to Israel and proposed that Egypt and Israel make peace with each other. The following year in negotiations at Camp David a peace treaty was negotiated and Israel returned the entire Sinai to Egypt, and Egypt became the first Arab state to recognize Israel and to comply with Res. 242.

The Golan Heights continues to be in Israel’s hands, and in 1981 it was annexed by Israel. In several negotiations in recent years Israel has offered to return this area to Syria but no agreement was reached and Syria continues to be at war with Israel, supporting terrorist attacks on Israel through Lebanon which it illegally controls and which is occupied by Syrian armed forces.

The main conflict today centers around the 1600 sq mi of territory west of the Jordan River that Jordan had occupied from 1949 to 1967. Since Jordan had thrown all the Jews out of that territory, in 1967 this area contained 600,000 Arabs and no Jews. During the 19 years the area was occupied by Jordan the population had declined because of Palestinian emigration. But beginning in 1967, because of the Israeli occupation, the outflow of Palestinians was reversed, and health conditions greatly improved, so that the Arab population has since grown to 2 million, and the Jewish population has risen to some 550,000 including the parts of Jerusalem added to Israel in 1967.

The Palestinian demand that Israel restore the ’67 borders would require that more than half a million people give up their homes and the neighborhoods and schools and synagogues they have built and lived in, on formerly empty land, most of them for more than 20 years, including more than half the Jewish population of Jerusalem.

The Jews settled in five groups of places outside the borders of 1967. First Jerusalem was unified and its borders slightly expanded to be more defensible and the newly acquired parts of it were annexed into Israel. Some 300,000 Israelis now live in parts of Jerusalem that had been occupied by Jordan from 1948 to 1967; the Palestinians refer to these residents of Jerusalem as “settlers.”

Second, several communities resettled places in the area of Gush Etzion from which Jews had been driven out by the Jordanian army in 1948. And a new suburban town, Efrat, was created in this area. This area, a few miles from Jerusalem, now has a Jewish population of about 30,000.

Third, two major suburban towns or cities were established, Ariel, 18 miles east of Tel Aviv, and Maale Adumim, 5 miles east of Jerusalem. Together these large towns have a population of close to 40,000. There are also perhaps a half dozen smaller suburbs of Jerusalem and Tel Aviv with up to 20,000 residents each, mostly just outside of the ’67 border of Israel.

Fourth there is the Jordan Valley which, except for Jericho, was empty in 1967, because essentially all the Arab population of the West Bank lived in the cities and villages near the ridgeline from north of Nablus to south of Hebron. Israel immediately decided that it would use the Jordan valley area to protect its Eastern border and established a series of farming communities in this flat, hot, arid below-sea-level area to anchor its military presence and support the protection of the border. And in addition some other small settlements were created on strategic hilltops overlooking the Valley.

Finally there are about a hundred smaller settlements. Most are very small communities located on hilltops between Arab villages or near Arab cities. Some were located for strategic reasons, others for religious. The Israeli communities established in Judea and Samaria, which is the traditional name for the West Bank, are built on land where there had been no Arab settlement. It was empty land, owned by the state and neither farmed nor used for pasture by the Arabs who had lived in nearby areas for generations. Altogether there are some 35,000 Israelis living in these smaller settlements which are separate from the main areas of settlement and from Israel – although some of them are small towns of several thousand people.

While generally the residents of the bigger, more suburban communities moved there to get less expensive space in rural surroundings, and the residents of the smaller settlements live there for ideological or religious reasons, there are many exceptions to both generalizations.

The result is a crazy quilt of Jews and Arabs living each surrounded by the other. There is no line that can be drawn to divide the groups so that each will live in a single contiguous territory. Especially so long as Israel stays in the Jordan Valley, either Jews will have to cross over Arab territory or Arabs will have to cross over Jewish territory, or both.

The Palestinians have several arguments to support their position. First, they say that all of Palestine (including the part which is now Israel) was theirs and wrongfully taken away from them – that is, that the League of Nations decision was wrong or invalid. Therefore, they say, that by accepting only the land that was outside of Israel before the war in 1967 they have given up 75% of their land and cannot be asked to compromise further. There are two problems with this argument: first, they never owned any part of Palestine to give up; and second, they never really gave up their claim to Israel, always teaching their children that all of Israel was Palestine.

The second Palestinian argument is that they interpret UNSC Res. 242 as requiring Israel to give up all the territories it acquired in 1967. But, as discussed before, that is not the meaning of Res. 242; it was not the intention of those who wrote Res 242, nor is it the words of 242.

Finally the Palestinians say that the Jews came to Israel as foreign colonizers who had no right to the land because Jews had never been in the land before the Arabs (Moslems) came to it. For example, they say, that what Jews call the Temple Mount never had a Jewish temple on it; it was empty land when the Arabs built the Dome of the Rock and El Aqsa Mosque in the 7th century. They deny that there is a Jewish people. They do not admit to their own people the historical reality that there are two peoples with deep roots in the land.

In fact Moslem sources have always recognized that the Dome of the Rock and Al Aqsa Mosque were built on the Temple Mount because it was a site that had been made holy by the Jewish temple. The recent Palestinian denial of an historical Jewish connection to the Temple Mount is also a denial of a Christian connection and a rejection of the New Testament’s reports of Christ at the Temple.

The Palestinians insist on “justice,” but they mean what would be just if the facts were what they tell their people. If the Jews were colonial strangers to the land, who came to take it from its Arab owners, without legal right or prior attachment to the land, then certainly justice would require that the Jews leave the land to its rightful owners.

The world decided in UN Res 242, as it had in the General Assembly partition resolution in 1948, that there are two peoples, Jews and Arabs with just claims to the land and that they must divide it between them. While the Palestinians have recognized that Israel exists they have never accepted that Israel and the Jews have legitimate claims in the land. They tell their people that Israel is a colonial invader with no roots in the land. It is hard to understand how there can be effective negotiations for Israel and Palestine to live in peace next to each other in this small piece of land before the Palestinians accept the legitimacy of the Jewish state and become willing to live in peace with it.

At the end of September 2000 after rejecting the proposal by Israel and the US to create a Palestinian state on more than 95% of the West Bank and Gaza plus the part of Jerusalem where Arabs now live, the Palestinians started a campaign of murder and terror against Israel. For a few months at the beginning of this campaign the Palestinians used crowds of civilians armed with rocks and firebombs, with snipers backing them up, and often with children in the front, to attack Israeli border guards or other targets. But after a short time the crowds dropped out and the attack was limited to individuals and small groups of shooters or bombers. They attacked cars and buses on the roads in the West Bank and Gaza, Israeli kibbutzim in Gaza, soldiers on or off duty in Israel and in the Gaza and the West Bank, and civilian crowds in places like pizzerias and cafes wherever they could be found in Israel. It was not an attack on the Israeli military and most of the victims were civilians, frequently women, children, and old people.

The Palestinians said that they were opposed to terror, but they argued that attacks against Israeli women and children was not terror because such attacks are Palestinian resistance to occupation. They view all disputed territory, that is, any place that they claim and that Israel doesn’t give to them, as occupied territory. (Their logic is that they regard it as their land, but it is controlled by Israel, so it must be “occupied land.”) And they regard any action they take against Israelis as resistance to occupation. By their definition whatever is resistance to occupation can’t be terrorism, even exploding bombs in discotheques in the heart of Israel.

To prevent terrorism Israel at various times prevented Palestinians from moving from one town to another, or established check points on roads that had been used to attack Israelis, or prevented Palestinians from coming into Israel. These and similar actions imposed great hardships on many Palestinians. And often checkpoints and inspections and other security measures were implemented by Israeli soldiers with disrespect or insults to Palestinians.

The Palestinians insist that none of the Israeli security measures are justified – because Israel has no right to defend against resistance to occupation – and so they feel that all Israeli security measures are acts of “terror” and aggression against the Palestinian people. In fact some of the “security measures” have little value for increasing security and are taken by Israel because of its frustration at not being able to stop Palestinian murder, and in hope that if the Palestinian population is sufficiently inconvenienced it will oppose the terror attacks that lead to the inconvenience and suffering.

An independent observer might try to evaluate Israeli security measures to decide which are reasonable steps to prevent additional murders of Israeli citizens, but the Palestinian position is that all Israeli security measures are gratuitous attacks against Palestinians for which Palestinians are entitled to take revenge by killing additional Israeli civilians. Thus subsequent attack on Israeli buses are not only legitimate resistance to occupation, but also justified retaliation for Israeli security measures (defined by the Palestinians as terrorism). What is often called the “cycle of violence” is a Palestinian bombing of a café, followed by an Israeli blockade of the town from where the bomber came, or an Israeli killing of a Palestinian terrorist leader, followed by a Palestinian bombing of a bus.

Israel says that terror attacks against civilians are different than attacks against terrorists, and are not to be weighed against each other. The Israeli view is that terror is wrong (and illegal) however just the cause for which it is being used, and that the victims of terror are morally and legally entitled to take whatever security measures (but not terror) are necessary to stop the terror. “Excessive force” means more force than necessary to stop the terror. Palestinians say that Israeli security measures are terrorism and that Israeli “terrorism” is not justified by Palestinian resistance to occupation.

In April, 2002, after the Palestinian terror campaign against Israel that had begun 18 months earlier culminated in a series of five suicide bombings in Israel in five days, killing over 100 people, including 29 who were attending a Passover supper in a hotel in Netanya, Israel began a massive campaign against the terrorist forces. The Israel army surrounded major Palestinian cities that had been the sources of the attacks on Israel and military units went into the cities to capture the headquarters and facilities of the Palestinian forces that had been attacking Israel. The Israelis captured and destroyed illegal weapons and workshops for the production of explosives for suicide bombers, and they arrested hundreds of Palestinians wanted for their crimes against Israelis and many of the leaders of the terrorist organizations.

Since some of the main terrorist bases were located in civilian areas, so-called “refugee camps,” and were protected by fighters and suicide bombers, as well as large numbers of mines and booby-traps, the Israeli operation was dangerous and time-consuming. The Israelis risked the lives of their soldiers to avoid using artillery and air power in ways that would have produced more Palestinian civilian deaths, and in Jenin alone lost 24 soldiers.

Israel has now adopted a policy of sending forces into the Palestinian occupied areas whenever necessary to capture leaders of the terrorist forces, to destroy important terrorist facilities, and especially to stop plans to bomb Israeli civilians. The result has been a drastic reduction in the rate of successful attacks against Israelis – although the number of foiled attacks demonstrates that the Palestinians have not ceased to try to kill as many Israelis as they can.

The war seems likely to continue at least as long as the Palestinians continue to get political and financial support from the democracies and from Iran and the Arab countries. Both the Palestinian leadership and population – if polls adequately reflect popular opinion – prefer fighting to living peacefully with Israel, even if the settlements have been removed and there is a Palestinian state with its capital in East Jerusalem. So Israel has to fight until there is a change in the situation, and it is now considering various ways to adapting to make the fighting less destructive.

http://www.simpletoremember.com/articles/a/what-the-fight-in-israel-is-all-about/

No comments:

Post a Comment